O

n her third day as the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Marcia Fudge phoned the White House. She had taken over an agency with a role to play addressing a range of crises as the lack of affordable housing in U.S. cities has left hundreds of thousands homeless and millions more in financial straits. She connected with Joe Biden’s climate team. Fudge and Gina McCarthy, Biden’s national climate adviser, talked about addressing climate change and the affordable-housing shortage at the same time. Three weeks later, the Administration announced plans to provide for more than 1 million resilient and energy-efficient housing units. “People are actually, from every agency, knocking on our doors,” says McCarthy, “wondering how they can be part of what is essentially a hopeful future.”

From her perch in the West Wing, McCarthy has been charged by Biden with overseeing a dramatic shift in the way the U.S. pursues action on climate change. Instead of turning to a select few environment-focused agencies to make climate policy, McCarthy and her office are working to infuse climate considerations into everything the Administration does. The task force she runs includes everyone from the Secretary of Defense, who is evaluating the climate threat to national security, to the Treasury Secretary, who is working to stem the risk that climate change poses to the financial system.

The approach “affords us the opportunity to be more than greenhouse-gas accountants,” says Ali Zaidi, McCarthy’s deputy. “We can tackle the breadth of the climate challenge and the opportunity if we map the intersections with housing policy, and the intersection with racial justice, and the intersection with public health.”

For decades, the idea that climate change touches everything has grown behind the scenes. Leaders from small island countries have pleaded with the rest of the world to notice how climate change has begun to uproot their lives, in areas from health care to schooling. Social scientists have crunched the data, illuminating how climate change will ripple across society, contributing to a surge in migration, reduced productivity and a spike in crime. And advocates and thinkers have proposed everything from a conscious move to economic degrowth to eco-capitalism to make climate the government’s driving force.

Now, spurred by alarming science, growing public fury and a deadly pandemic, government officials, corporate bosses and civil-society leaders are finally waking up to a simple idea whose time has come: climate is everything. It’s out of this recognition that the E.U. has allocated hundreds of billions of euros to put climate at the center of its economic plans, seemingly unrelated activist groups have embraced environmental goals, and investors have flooded firms advancing the energy transition with trillions of dollars. “The world is crossing the long-awaited political tipping point on climate right now,” says Al Gore, a former U.S. Vice President who won the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his climate activism. “We are seeing the beginning of a new era.”

The course of climatization—the process by which climate change will transform society—will play out in the coming years in every corner of society. Whether it leads to a more resilient world or exacerbates the worst elements of our society depends on whether we adjust or just stumble through. “We are at the point where climate change means systems change—and almost every system will change,” says Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University and a longtime climate leader. “That understanding is long overdue, but I don’t think we know exactly what it means yet. It’s a moment of maximum hope; it’s also a moment of high risk.”

The basis for human civilization was laid roughly 10,000 years ago when, after tens of thousands of years of unpredictable weather, the earth’s climate stabilized: weather extremes became more manageable, and humans began to practice agriculture. The global population grew from fewer than 10 million people 10,000 years ago to more than 7.7 billion today. We have a buzzing global economy measured in dollars and cents, but our economic system has failed to account for the role a stable climate played in creating it.

For decades, scientists, activists and economists have warned of growth without concern for the consequences. Simon Kuznets, the Nobel Prize–winning economist who conceptualized GDP, warned in the 1960s that “distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and return.” Gore cautioned in his 1992 book, Earth in the Balance, that humans need to make the “rescue of the environment the central organizing principle for civilization” or risk losing everything. In 2006, The Stern Review, a groundbreaking report from a group headed by former World Bank chief economist Nicholas Stern, found that climate change could drive a 20% decline in global GDP. And in 2014, author and activist Naomi Klein wrote This Changes Everything, arguing that climate change required a reimagination of our economy. Still, for a time, the issue remained a marginal concern for most.

Over the past three years, that has begun to change, at first slowly and then suddenly. In 2018, the U.N. climate-science body published a landmark—and chilling—report warning of a looming catastrophe if the world didn’t accelerate the pivot to a low-carbon economy. Protesters took to the streets around the globe. First in Sweden and then on the global stage, Greta Thunberg decried the pursuit of growth without concern for looming catastrophe. In the U.S., the Sunrise Movement, a youth activist group, called for a Green New Deal that would put climate at the center of the American economy, melding action on climate change with progressive priorities. “The climate crisis touches virtually every part of our lived experience, whether it’s our health, or our jobs and the economy,” Varshini Prakash, a Sunrise Movement co-founder, told TIME in 2019, calling the Green New Deal a “decades-long project to revitalize our economy, to stop climate change and to ensure racial and economic equity.”

When COVID-19 hit, the climate conversation at first took a back seat as hospital beds filled. But in the midst of the crisis, interest seemed only to grow as the pandemic reminded people of the risk of ignoring science and the world’s interconnectedness. Ahead of the U.S. presidential election, polls showed American voters more concerned about climate change than ever before, and as the pandemic devastated economies, leaders around the world promised to rebuild with climate change in mind. “People are suddenly reflecting: What kind of society, what kind of world, what kind of economy are we living in?” says Achim Steiner, head of the U.N. Development Programme. “Climate change suddenly has become a vehicle of green recovery.”

Many countries have yet to match the rhetoric with action. A February report from the U.N. found that emissions would decline just 1% by 2030 with nations’ commitments, though that estimate notably didn’t include countries like the U.S. that had yet to share their plans. But the understanding that halting warming will require considering climate across the economy is now all but universally accepted on the global stage. Unthinkable just a couple of years ago, political leaders have bet their countries’ economic futures on climate-fighting measures. “Action on climate is not only necessary for the future of our lives and livelihoods,” says Stern. “Climate action is the main engine of growth; it’s the growth story of the 21st century.”

There is no doubt that the sharpest turnaround is in the U.S., where a President who denied climate change was replaced by one who has made it an organizing principle of economic policy. The Biden Administration’s proposed $2.65 trillion infrastructure package, intended to lift the U.S. out of its COVID-driven recession, calls for $174 billion to “win” the electric vehicle market, $35 billion for climate-related research and development, and $100 billion to advance clean energy on the electric grid. Even aspects of the plan that seem unrelated to climate—roads and bridges, housing and broadband—have a climate angle. Transportation infrastructure will be built with resilience to climate risks, new affordable housing will be energy-efficient, and broadband will aid low-carbon industries. More than half of the spending is “clean and climate-friendly,” according to a World Resources Institute analysis.

Crucially, a slew of initiatives apart from the infrastructure package seek to address the economic costs of climate change. Flood-insurance premiums are set to rise to reflect flood vulnerability. Financial regulators have begun pushing new rules to require companies to disclose climate risk. In a far-reaching move, the Administration is calculating a new figure to represent the economic cost of each ton of greenhouse-gas emissions. That figure—which could double the level set by Obama—will inform government spending, requiring the rejection of some programs in which the climate costs outweigh economic benefits. “The output of good economic policy is good climate outcomes,” says Zaidi.

In the E.U., top officials recount awakening to the need to embrace climate change as a development framework while they prepared for the 2015 climate negotiations that delivered the Paris Agreement. As the European Commission—the bloc’s executive body—searched for a path to eliminate the E.U.’s carbon emissions, officials convened a process in which each country dug into its own emissions. They concluded that to cut emissions on the scale required meant incorporating climate across all facets of government. “It permeated down from the top governmental level to all other departments, to the societies, to the industrial stakeholders,” says Maros Sefcovic, a vice president of the European Commission who ran the process.

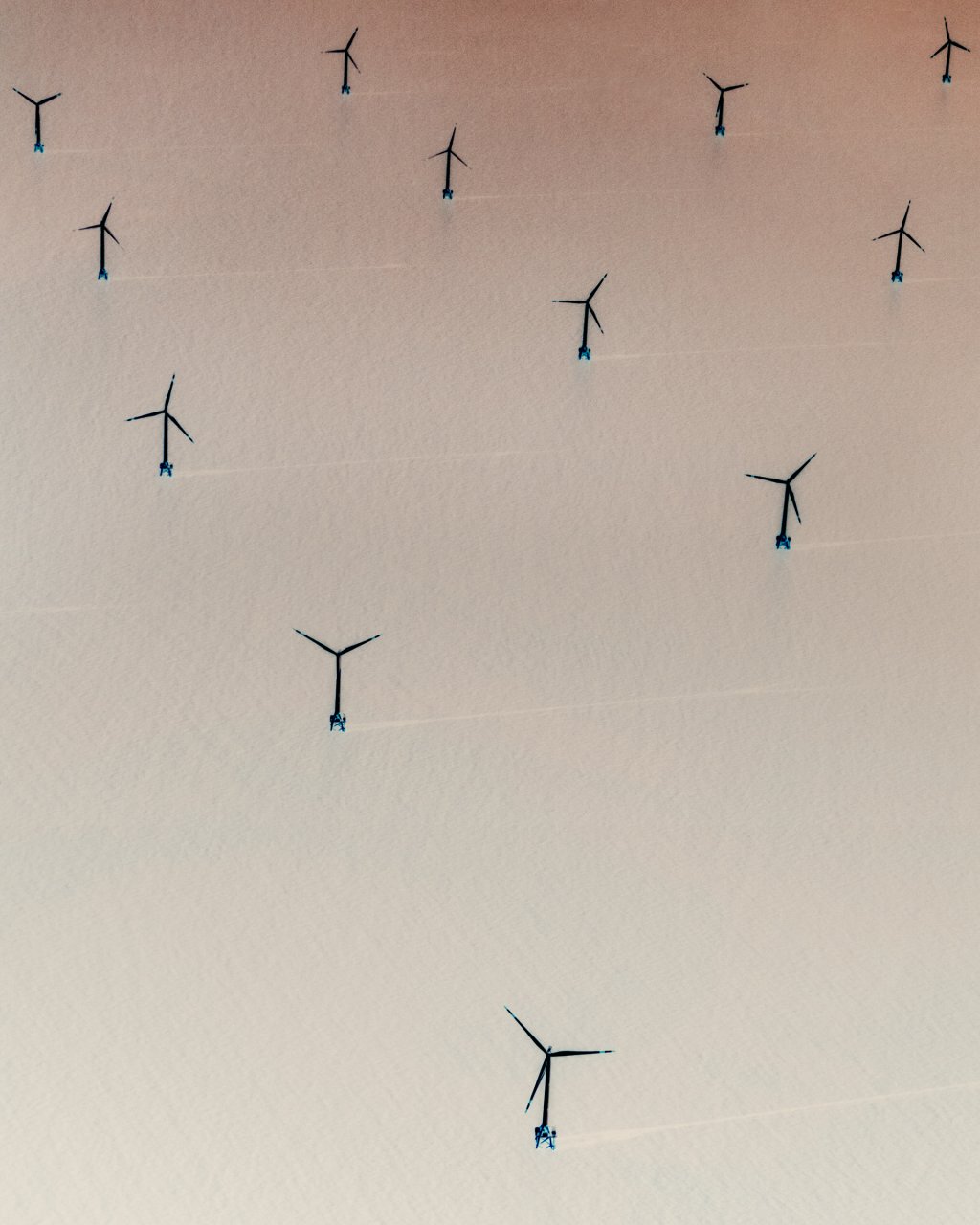

Five years later, the COVID-19 pandemic has given the E.U. the perfect opportunity to accelerate the remaking of its economic agenda with climate at its core—what Sefcovic calls the “new economy of the 21st century.” The European Commission framed its pandemic-relief program around a so-called Green Deal that aims to invest hundreds of billions of euros in everything from zero-emission trains to growing renewable-energy capacity. But its true aims are more ambitious than any line item. “If you want to succeed, you have to successfully transform all sectors,” says Jeppe Kofod, Denmark’s Foreign Minister. “I call it a climate union.” A successful centering of climate would place the E.U. at the center of the global economy, setting standards for the world.

Still, the climatization path is not universal progress. Countries can simultaneously invest in a clean economy and continue to prop up polluting industries. In China, the world’s largest emitter and second largest economy, officials have made the transition away from high-carbon industries central to development, spending hundreds of billions of dollars to build manufacturing capacity for electric vehicles, solar panels and other clean-energy technology. Recently, it has focused on growing services and the Internet economy—rather than carbon-heavy industry. Still, the country continues to finance fossil-fuel development abroad, potentially leaving debtor countries stuck with coal plants and oil pipelines. In the U.S., too, the Biden Administration’s focus on expanding clean energy without a more targeted effort to shut down fossil fuels has drawn criticism from climate advocates while the E.U.’s continued reliance on natural gas has done the same across the Atlantic.

These differing approaches to climatization have created a new vector for collaboration as well as conflict. One country’s efforts to reduce emissions only matters if the whole world moves, and so as countries prioritize climate change in their own economic planning, pressure has grown to ensure others follow suit. The E.U. has begun the process of linking its climate and trade agendas with a tax on high-carbon imports, penalizing countries slow to act on climate change. Biden has elevated the issue as a diplomatic priority. “Every dialogue that we have we’re trying to drive ambition,” says John Kerry, Biden’s climate envoy and a former U.S. Secretary of State. And many of the multilateral financial institutions that fund economic programs in developing countries have required projects to adapt to new climate realities while addressing other needs. “If we are going to bail out a private-sector organization or company, they should commit to using those resources in a way that is climate-friendly,” says Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, the head of the World Trade Organization and a former Nigerian Finance Minister. The task couldn’t be more urgent. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, finance ministers say that in somes cases they are already spending 10% of GDP on climate adaptation—a figure that’s only expected to grow with time. And that’s just a glimpse of what’s to come elsewhere.

The intertwining of the economy and climate change promises to shape global politics and society for the foreseeable future. “This is going to be the topic that dominates everything,” says John Podesta, the longtime political operative who served in both the Clinton and Obama administrations. “The effects on the natural world that result from climate change are going to be central to both the political conversation and how we organize ourselves as a society for at least the next 30 years.”

Since World War II, the pursuit of economic growth has driven politics. In democracies, citizens look at their bank accounts as a proxy for quality of life, rewarding politicians in boom times and voting them out when times get tough. In authoritarian countries, slow economies have doomed regimes. Political consultant James Carville, who advised President Bill Clinton, put the dynamic simply, before the 1992 election: “It’s the economy, stupid.” People will undoubtedly continue to prioritize their own bottom line—thinking about jobs, investments and retirement. But as the effects of climate change increasingly shape economic outcomes, we may soon be saying, “It’s the climate, stupid.”

When Steve Schrader began pitching his company’s latest electric truck to potential clients, he focused on the bottom line: a Workhorse rig would save $170,000 per vehicle over 20 years. But his potential customers wanted to hear about emissions. In a survey, customers ranked the vehicles’ environmental impact as their top concern. “That kind of surprised us,” says Schrader, Workhouse’s chief financial officer. “We thought people kind of paid lip service to it, but apparently it’s very important to them.”

Though climatization is just beginning, its effects are already spreading. Companies are scrambling to remake supply chains, unions are bracing for a change to the labor market, and activists are grappling with how climate change will reshape their long-standing missions. For these groups and many others, this adjustment brings enormous promise as climatization offers an opportunity to rethink the way things work for the better. But there’s no guarantee, and the uncertainty brings peril too.

That’s especially true in the transportation sector. Throughout the Trump years, automakers fought Obama-era fuel-efficiency regulations. Within a few months of Biden’s election, automakers dropped their fight and committed to going electric. This has far-reaching implications for an industry that employs close to a million workers manufacturing cars in the U.S. and millions more selling and repairing them. Electric vehicles look largely the same as their gas-powered counterparts, but they are different machines. Auto companies have searched urgently for software engineers, while internal-combustion-engine experts have had to pivot. Unions and the local communities that the industry has called home for decades are now bracing for the transition. On the one hand, climatization for the auto industry will bring new investment. On the other, workers may be displaced because electric-vehicle manufacturing is less labor-intensive.

Similar transformations are happening across the economy. Driven by a mix of government pressure, client sentiment and investor demand, companies are rethinking operations to adapt to a climate-changed world. Construction firms have begun adapting buildings to protect against climate impacts while grappling with pressure to build sustainably. Some oil and gas majors have begun to shift billions of dollars toward natural gas, plastics and renewables while their core oil business struggles. Major technology firms are seeing a spike in demand from their corporate clients to build climate into their products. “It’s a core customer issue now,” says Michelle Patron, director of sustainability policy at Microsoft. “We’ve seen sustainability and climate come out over the last few years, from the [corporate social responsibility] space and the compliance space to really be mainstreamed across the business.”

The shift for advocacy and activism may be just as profound. On a slew of issues, from immigration to housing, activists have been working slowly but surely for decades to make progress around key plans, proposals and laws in their areas of focus. But in recent years, climate change has become unavoidable.

Jacqueline Patterson hadn’t positioned herself as an environmentalist when she was asked to lead the NAACP’s climate-justice program in 2009. A former Peace Corps volunteer, Patterson had spent much of her career working on gender and health, but climate change just kept coming up. She worked with communities vulnerable to extreme weather in Jamaica and saw the disproportionate impact of Hurricane Katrina on the Black community in New Orleans. When she took the NAACP job, she thought she would launch the program and then leave. A decade later, she’s still there, and the NAACP has embraced climate action as part and parcel of racial justice. Patterson lists a dizzying number of programs the organization runs at the intersection of the two issues: an initiative to help the Black community access the green economy, another to look at the effect of fossil-fuel pollutants on children’s educational performance and another to study the use of prison labor to fight climate-related disasters. “Economy, food, housing, transit—all of these are civil rights issues,” says Patterson. “And climate issues intersect with every single one.”

Institutions across the world of advocacy and philanthropy have woken up to these connections. Oxfam is centered on ending global poverty. It also works on climate change. UNICEF provides aid for children around the world. It also works on climate change. The Kaiser Family Foundation targets health policy. It also works on climate change.

On my last reporting trip before COVID-19 took hold, I took the train to Philadelphia to observe a focus group designed to glean views on climate change in the local Black community. At first, participants largely avoided talking about the issue—instead focusing on racial justice, crime and employment. But over the course of 90 minutes, participants started to consider how warmer temperatures might lead to a spike in crime, citing their own experience with crime on hot days. They talked about their worsening allergies, speculating that allergy season had lengthened. And they noted the solar panels popping up across the city. These observations aren’t the textbook examples of climate change—the rising seas, record storms and giant wildfires—but they are results of climatization. Allergy season is indeed getting longer because of warmer weather, research has shown rising temperatures will likely drive increased crime, and obviously the move to renewables to stem emissions has led to policies to promote solar panels. In the end, many left the focus group saying they wanted to learn about the Green New Deal, fracking and environmental justice. “You’re going to have me Googling when we leave,” one participant remarked.

If you don’t already, with a little prodding, you too may notice the signs of climate seeping in your world. Maybe it’s the improved fuel economy on your latest car, driven by regulations intended to reduce transport emissions. (In fact, many major consumer electronics products—from your refrigerator to your TV— have been subjected to energy efficiency rules.) Or perhaps it’s the cost of flood insurance, which in some places in the U.S. will spike this year to address the increased risk of floods. If you live in a city, bike lanes might have popped up in the city center, a COVID-19 adaptation that many mayors have vowed to keep and expand with climate in mind. The list goes on—and is destined to grow.

Many who oppose climate policy would undoubtedly take issue with the notion that climate should be addressed in all elements of our economy and society. For years, that rejection was rooted in a denial of climate science. But in recent years, as public understanding of climate change has grown, that position has become increasingly untenable, and opponents of climate action have offered their own vision of climatization. In a 2019 op-ed, Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, for example, acknowledged that flooding would increase in the state and cited predictions that the “30-year mortgage will die out” in some parts of Florida because of climate risks. He proposed adapting, to “buy time.” That same year, then U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo celebrated new trade routes that would open in the normally frozen sea as a result of climate change. “This is America’s moment to stand up as an Arctic nation,” he said, describing the region as “an arena of global power and competition.” In these visions, climate change is taken for granted—and we are all left to play a game of survival of the fittest.

Such a game wouldn’t just pit countries against one another—it would also pit humans against the planet. And the planet would win every time. In a 2010 study, researchers looked at the ancient city of Angkor, the capital of the Khmer Empire (in modern-day Cambodia), for some 600 years beginning in the 9th century. Angkor was a sophisticated city with hundreds of thousands of residents—until its collapse. Since then, accounts have attributed the decline primarily to conflicts with a neighboring kingdom and shifting trade patterns. But recent research suggests that climate—specifically, a decades-long drought as well as monsoons in the 15th century—needs to be considered among the other challenges. “We can be tempted to look at the historical record and be like, ‘Those guys didn’t know what they were doing, but we are super sharp now,’” says Solomon Hsiang, a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley. “I’m pretty sure those guys thought the exact same thing.”

Hsiang’s recent research has shown the subtle effects of climate change—increased crime, lost labor productivity and increased mortality, to name a few—would devastate society, slashing economic output and leading to something like a permanent recession. “A lot of ways in which climate change is really bad are like death-by-1,000-cuts situations in which we don’t realize we’re being affected by the climate,” he says.

Back in D.C., McCarthy and Zaidi tread carefully when asked about the costs of climate change, which both note are piling up, before shifting the conversation to a more positive vision. “That’s why so many people are getting interested in the issue of climate change,” says McCarthy. “Because it’s now being presented as an opportunity. It’s now being presented as a hopeful message.” Two things can be true at once, and the future brought about by climatization may very well include elements of both visions: crushing economic effects as well as opportunities for rejuvenation. Indeed, as the effects of climate change become more apparent and the response becomes more urgent, it’s almost inevitable. But both must be considered; only by recognizing how climate will seep into everything can we tilt the scale toward something a little better.

—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Alejandro de la Garza/New York

soucres: https://time.com/5953374/climate-is-everything/

Read more: